By Aditya Kiran Kakati and Catriona Child

Some years ago, during our fieldwork, Jeremiah Pame, an assistant professor at Delhi University and a Zeme Naga community leader and the President of the Zeme Olympics Association, told us: “On meeting another Zeme, the first one would simply ask: What village are you from? In those days, land was not measured in kilometers but from mountain to mountain or river to river. There was no concept of state boundaries (except village boundaries) cutting across the Zeme lands.”

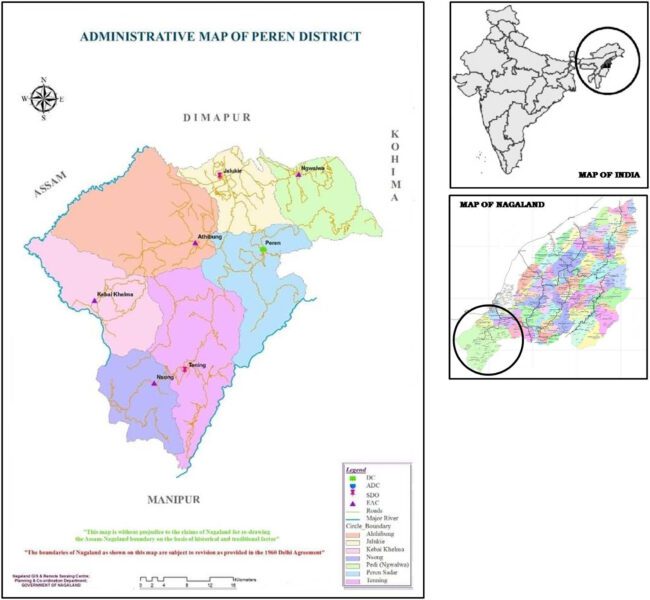

In this way, Jeremiah explained the rationale behind the first Zeme Olympics, held from 10 to 17 December 2019 in the town of Jalukie, Peren District, Nagaland, India (see map). The Zeme are one of around 35 Naga tribes that inhabit the northeast Indian states of Arunachal Pradesh, Assam, Nagaland, and Manipur. Jalukie, located in the southwest of Peren, lies close to the confluence of the borders of three of these states—Assam, Manipur, and Nagaland. Zeme Naga communities (today over a hundred thousand strong) historically inhabited this contiguous hilly area before the creation of various borders by the British and, later, the postcolonial Indian state.

Map extracted from Jamir et al. 2022

The Zeme Olympics, conceived and driven by Jeremiah, and supported by elders of the tribe and a team of young organizers, was a response to the historical marginalisation that Zeme communities have faced in all the states they inhabit. Previous events in 2012 and 2013 arranged by Jeremiah and his colleagues had focused on bringing the Zeme from Assam, Manipur and Nagaland together at large-scale winter gatherings to socialise and celebrate their unique culture. As Jeremiah explained to us, the drawing of inter-state boundaries has made the Zeme minority “backward” communities within the Naga groups of India. Tribal boundaries in Naga territory are a product of colonial ethnology and frontier policies (Robb 1997; D. Das 2014). These boundaries continue to be malleable and inventible, depending on local groups’ attempts to seek developmental goods and privileges from the state (Wouters 2017a; Karlsson 2003). Additionally, inter-personal village and clan-level identities often take precedence over top-down tribal and ethnic identities in how Nagas relate to spaces, as Jeremiah’s statement above explains (Wouters 2017b; Chophy 2022). Moreover, within the state of Nagaland, Nagas have strategically negotiated protective provisions in the Indian Constitution that guarantee ownership and control of resources (similar protections do not apply to Nagas living in Assam and Manipur, many of whom are Zeme). For the Zeme, their marginalisation within Naga politics is evidenced by the fact that they remain excluded and disadvantaged within India’s “internal borderland” regimes. These regimes determine taxation, legal rights, customary law, and resource access, apart from territorial land (Wouters and Tunyi 2018). Within the various borders in the Northeastern Indian states that determine access to equitable development and economic opportunities, the Zeme Nagas are often disadvantaged.

Jeremiah says that even when the state boundaries were crystallised post-Independence, particularly after Nagaland state’s creation in 1963, the Zeme people did not notice them much, even though their domain had been divided into three states. He added, “It wasn’t really until the 1980-90s that the Zeme began to notice the effects of the boundaries because, by then, the political effects… of being a minority community in each of the three states had begun to become obvious.” Over and above the drawing of border lines on a map, it is the political baggage— laws, benefits, resources, priorities, and privileges—accompanying these borders that matters. These elements heighten the divisions within a community like the Zeme. It sharpens existing inequalities; for instance, we were told by our interlocuters that the Zeme in Nagaland, concentrated in the Peren district, generally receive a better education than those in Manipur or Assam. Anthropologist Avitoli Zhimomi, Jeremiah’s wife, gave us an example of Zeme marginalisation within Manipur. She explained that, in Tamenglong town, the Zeme are usually in the minority and thus have to learn the languages of the more dominant Naga tribes, such as the Rongmei, in school. She also said that the Zeme in Tamenglong tend to be economically disadvantaged relative to other tribes. For instance, the Rongmei owned land in the area, while the Zeme were only there as workers, not landowners.

Avitoli pointed out the tendency among tribes to bolster their tribal identities to access state resources and mitigate feelings of group insecurity. The Zeme Olympics was an example of a community seeking to generate greater group cohesion to combat external pressures. Jeremiah told us that he primarily viewed the Zeme Olympics event as a “confidence-building” exercise. He mentioned that when over ten thousand Zeme attended the Opening Ceremony, the community suddenly realised they had politically significant numbers. If you add all the Zeme across the three states, it comes to a hundred thousand. With this population, the Zeme could be a significant Naga tribe, like the Angami in Nagaland, who number three hundred thousand. Internal state borders may have separated the tribe, but the convergence in Jalukie potentially allowed the people to engage with each other as a transborder community. However, this could be challenging since many Zeme teams (representing individual villages or towns) required interpreters to communicate with each other.

Dungki FC Wome’s Football team at the Jalukie market with their coach and film crew member

Jalukie lies on the periphery of the Zeme traditional lands, but its hosting of the Zeme Olympics arguably lent it an aura of centrality, at least for the thousands of Zeme who gathered here for the event from across the three states. A peripheral and remote interstate border-proximate town became a new hub of activity. According to Jeremiah, Jalukie’s favourable border location and relative accessibility through interior inter-state roads (albeit, back-breaking ones) made it a suitable location for this event. Its flattish terrain on a plateau was an added advantage. As Jeremiah explained, the level terrain meant Jalukie offered several usable and accessible grounds for such a large-scale sports event, facilities that would be absent from most Zeme villages in the hills. The events included “indigenous” ceremonies (like Traditional Fire Making and Rehoi, the traditional “war cry”) performed during the Opening Ceremony and sports like Naga Wrestling, Bamboo Stilt Race, and Battle of the Horn (or Mpei Kaube, in which a freshly killed ceremonial Mithun bison head is strung up and competitors jump to reach and hold on to it). Other “popular sports” like football, volleyball, marathon, sprint, shot put, and long jump were among the many competitive events at the Zeme Olympics.

Battle of the Horn (Women’s competition)

Jeremiah said that he was motivated by the desire to create a forum for grassroots-level engagements, and he stressed that the event was primarily funded through crowdsourcing. His idea departed from elite-driven trans-border initiatives undertaken by the various Church denominations, which encourage thinking along other axes of imagined sovereignty and alternative maps of community solidarity. G. Kanato Chophy proposed the idea of the “Baptist Highlands” cutting across interstate and international borderlands as an example of an alternative cartography in the Naga context (Chophy 2022). Naga activists like Visier Meyasetsu Sanyu have long explored de-territorialised models of sovereignty, inspired by the Sami communities spread across Norway, Sweden, and Finland. This idea is endorsed by scholars pointing out that the Zeme case could be a step forward in thinking about such a model due to the community’s territorial exclusion (N. K. Das 2018). Most significantly, the Zeme Olympics event allows us to explore alternative notions and practices of sovereignty beyond predominant nation-state or ethno-territorial concepts. Jeremiah believes in “practical” not “theoretical” Zeliangrong—the notion of Zeliangrong referring to the umbrella category encompassing the three Naga tribes of Zeme, Rongmei, and Liangmai, who are spread across the Assam-Manipur-Nagaland borders and claim a common ancestry. He feels that “practical Zeliangrong” is an attractive political concept that could potentially allow greater leverage against state institutions. However, he feels that, in reality, it would only serve to exacerbate existing conflicts between the three related tribes by generating struggles for dominance. Moreover, during an interview during the shoot for the film, We, the Zeme, he emphasised the non-elite focus of the Zeme Olympics, which was aimed particularly at non-elite individuals and groups (Alison Kahn 2021).

Jeremiah (far left) and Catriona (far right)

The Zeme Olympics served as a lens through which the hegemony of the internal borders of a nation-state could be viewed. It also constituted an interesting departure from the usual focus on international boundaries in borderland studies. Moreover, the event presented unique axes of solidarity as well as opportunities to consider sovereignty and group solidarity questions. We may think about how grassroots community-led events can challenge the imposed hegemonies of borders.

References:

Alison Kahn. 2021. We, The Zeme. Privately Published. https://video.alexanderstreet.com/watch/we-the-zeme.

Chophy, G. Kanato. 2022. “Ethnic Attachments and Alterations among Nagas in the Indo-Myanmar Borderland.” In Routledge Handbook of Highland Asia. Routledge.

Das, Debojyoti. 2014. “Understanding Margins, State Power, Space and Territoriality in the Naga Hills.” Journal of Borderlands Studies 29 (1): 63–80. https://doi.org/10.1080/08865655.2014.892693.

Das, N.K. 2018. “Sovereignty Question and Culture Discourse: Interrogating Indo-Naga ‘Framework Agreement’ in Relation to Naga Movement Published by: Indian Sociological Society.” Explorations Vol. 2 (2), October 2018 (October): 39–69.

Karlsson, Bengt G. 2003. “Anthropology and the ‘Indigenous Slot’: Claims to and Debates about Indigenous Peoples’ Status in India.” Critique of Anthropology 23 (4): 403–23. https://doi.org/10.1177/0308275X03234003.

Kizukala Jamir, Kottapalli Seshagirirao, and Maibam Dhanaraj Meitei, “Indigenous Oral Knowledge of Wild Medicinal Plants from the Peren District of Nagaland, India in the Indo Burma Hot-Spot,” Acta Ecologica Sinica 42, no. 3 (June 1, 2022): 206–23, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.

Robb, Peter. 1997. “The Colonial State and Constructions of Indian Identity: An Example on the Northeast Frontier in the 1880s.” Modern Asian Studies 31 (2): 245–83. https://doi.org/10.2307/313030.

Wouters, Jelle J.P. 2017a. “The Making of Tribes: The Chang and Chakhesang Nagas in India’s Northeast.” Contributions to Indian Sociology 51 (1): 79–104. https://doi.org/10.1177/0069966716677406.

———. 2017b. “Who Is a Naga Village? The Naga ‘village Republic’ through the Ages.” The South Asianist 5 (1).

Wouters, Jelle J.P., and Zhoto Tunyi. 2018. “India’s Northeast as an Internal Borderland: Domestic Borders, Regimes of Taxation, and Legal Landscapes.” The NEHU Journal 14 (1): 1–17.

Note: All images are taken by Aditya Kiran Kakati (and owner of copyright).