By Leonie Arendt

BA Cultural Anthropology and Development Sociology, University of Amsterdam

As an anthropologist, you live for and by questions! So, “What does it mean to ‘belong’ in a place where national borders exist, but don’t dictate daily life?” That was the question I found myself returning to during my internship at the EUREGIO office in Gronau, a small German town nestled right along the Dutch border. I had entered the internship hoping to explore how institutions like EUREGIO manage the tensions and possibilities of cross-border cooperation, not just as policy, but as lived experience.

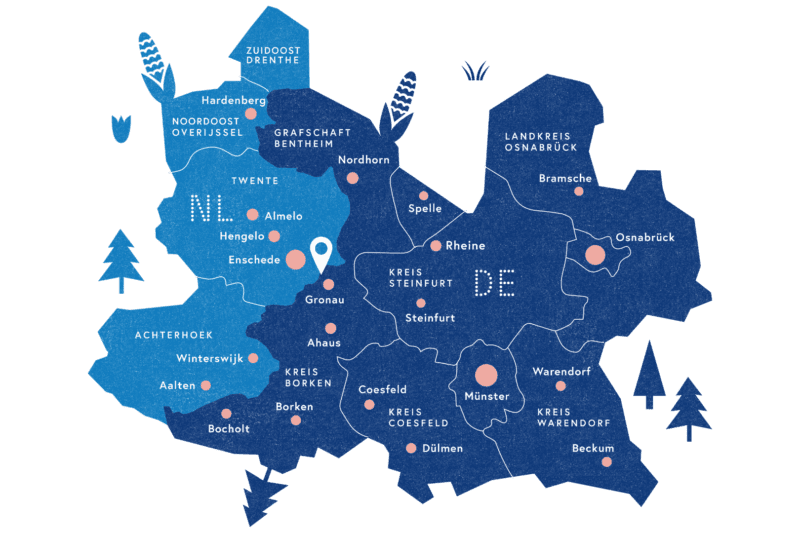

EUREGIO, established in 1958, is one of the oldest cross-border organisations in Europe. Its aim is straightforward: to promote regional collaboration between municipalities in the Netherlands and Germany. What makes it unique is that it doesn’t approach borders as problems to fix or barriers to erase. Instead, it focuses on creating pragmatic, everyday structures for cooperation, joint projects in infrastructure, education, healthcare, art, culture, and more, that allow the region to function as a shared space.

Map of the EUREGIO area

The organisation’s headquarters in Gronau itself embodies this idea. The working language is both German and Dutch. Conversations often flow between the two languages depending on who is in the room, and while most employees are comfortable in both, there is very little English spoken. At first, this surprised me. As a student used to international academic settings where English dominates, the absence of it was noticeable. But soon, I understood that this isn’t about internationalism in the abstract. Rather, it’s about building regional familiarity, rooted in local languages and cultural rhythms.

Seeing the border from the inside

From an anthropological perspective, the way EUREGIO functions is deeply revealing. Take the GrenzInfoPunkt (GIP), for example. This service centre provides practical support for people living or working across the Dutch-German border, covering everything from taxes and healthcare to pensions and employment contracts. These issues are often framed as bureaucratic, but for people who cross borders every day, physically, socially, economically… they are incredibly personal. The GIP is not simply about providing information. It’s about creating security in ambiguity. It reflects the reality that for many in this region, belonging is negotiated across two systems, two languages, two sets of expectations.

I also had the chance to sit in on several internal meetings and discussions with partner municipalities. There, I saw how cross-border cooperation isn’t always smooth, it’s a process of negotiation, compromise, and learning how to listen across difference. But I also saw something else, and that is a clear sense of regional identity among many of the staff. They didn’t just work in a cross-border context; they saw themselves as part of a cross-border region. Their biographies, their families, their daily routines… they were shaped by the ebb and flow between the Netherlands and Germany. That kind of belonging isn’t created by treaties or top-down initiatives! It’s slowly grown, encounter by encounter, over decades.

Borderlessness, unevenly felt

But that sense of cross-border identity isn’t universal. During my internship, I visited a school in Gronau and spoke to students about how they experience the border. Their responses were varied, but one thing stood out: for many, the border still felt real. Some students had never been to the Netherlands, even though it was just a few kilometers away. Others mentioned language as a barrier. You see, Dutch is not taught in all schools, and not every young person grows up bilingual. Some simply didn’t feel any personal connection to “the other side.”

Students discussiong euregional ideas during project day in Gronau

This discrepancy brought me back to a key anthropological tension – just because something exists institutionally doesn’t mean it’s felt equally by everyone. While EUREGIO does a great deal to foster practical and symbolic integration, not everyone inhabits the border the same way. Age, class, education, and geography all influence whether people experience the region as “borderless” or still divided.

A region built on relationships

What this internship ultimately offered me was a more grounded understanding of how borders work, not just as geopolitical markers, but as shifting cultural fields. EUREGIO’s work is about building relationships, between people, between towns, between administrative systems. That relationship-building is not always perfect, and it’s rarely quick. However, it’s deeply human.

And oh, there’s often a tendency to talk about “Europe” in grand, abstract terms. What I appreciate about EUREGIO was that it wasn’t interested in abstraction. It was interested in buses running on time between towns, in artists from both sides of the border exhibiting their work together, in people understanding where to file their taxes when they live in one country and work in another. These small things matter. For real, they do. They create trust. They allow belonging to take root.

As an anthropologist, I’m used to thinking critically about institutions and identity. This experience reminded me that sometimes, the most important insights don’t come from critique, but from observation, from paying attention to the quiet, everyday ways people try to make complicated systems work better. EUREGIO may not be perfect, but it shows that even in a world of borders, cooperation is possible, and that belonging doesn’t have to end at a national line. I’m genuinely grateful for the chance to work alongside the people at EUREGIO; what I learned all through is something I’ll hold on to for a very long time.