This work by Gwen Petrina Latenri Tappu is the first runner-up essay of the Eur-Asian Border Lab’s 2025 volumetric borders essay contest

Gwen Petrina Latenri Tappu is a driven medical student from Indonesia with academic interest in neurological surgery and clinical research. She also explores global health and interdisciplinary research, engaging in how medical science intersects with societal narratives and lived experiences across borders.

I. Introduction – Where are the borders now?

Historically, “borders” conjured images of lines on a map dividing nations. In healthcare, these once seemed clear: the hospital’s location, the physician’s practice, the patient’s body. Today, amid pandemics and digital surveillance, borders have multiplied, becoming not only territorial, but also organic and virtual, with profound political significance.

The COVID-19 epidemic showed limitations in global health and how power impacts access. The rights to breathe, travel, and receive medical treatment are contingent upon geographical location, algorithms, passports, and regulations. Digital exclusion is as tangible as physical obstacles, with individuals influencing access to testing, vaccination, or healthcare services. Borders now encompass biological, digital, and geopolitical barriers impacting individuals, data, and legislation.

This essay contends that emerging borders, whether biological, digital, or geopolitical, are reshaping healthcare accessibility, mobility, and exclusion. Health encompasses not only medicine and infrastructure but also the regulation of bodies, signals, and access points. Comprehending these multifaceted barriers is essential for constructing equitable healthcare systems that tackle structural exclusion.

|

|

|

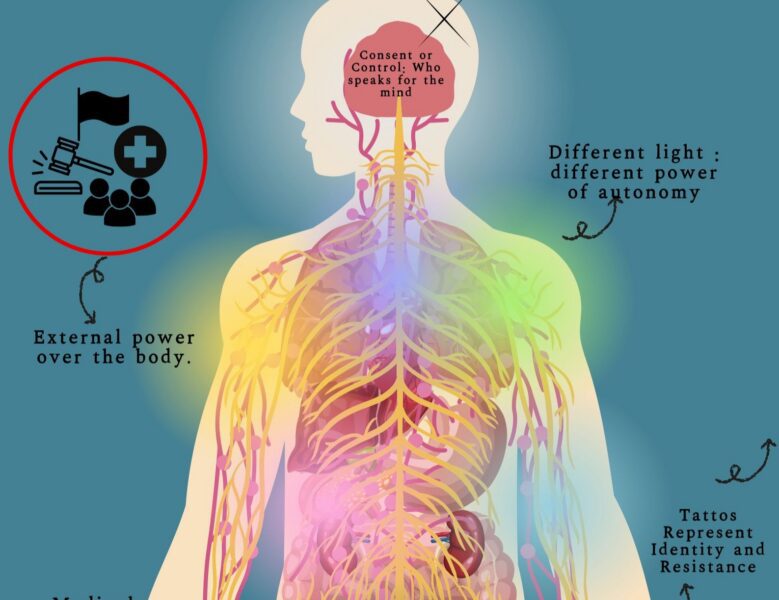

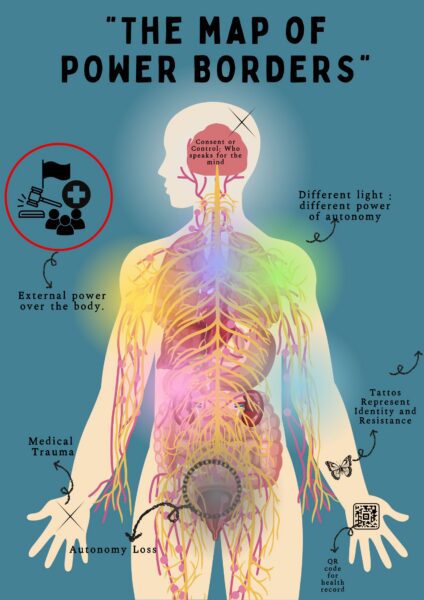

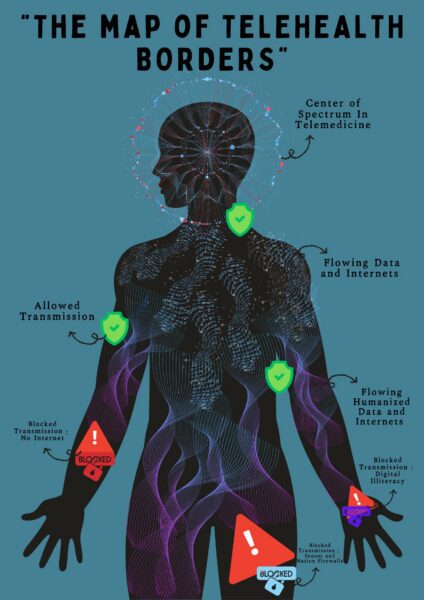

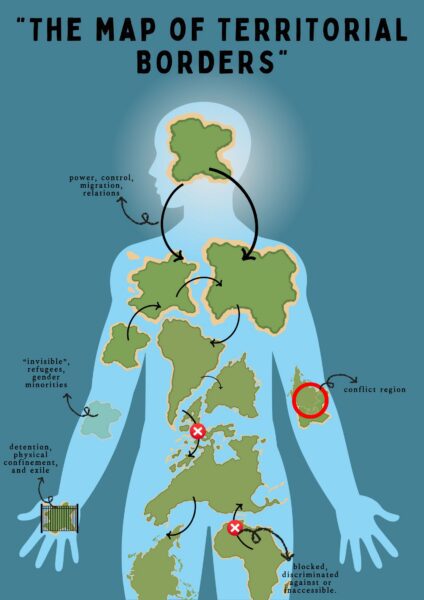

Figure 1. Conceptual visualization of healthcare borders

A. The map of power borders – reflecting political, legal, and biopolitical control over the body; B. The map of telehealth borders – illustrating digital barriers and technological divides in healthcare access; C. The map of territorial borders – showing geopolitical and geographical constraints on healthcare mobility. Visuals designed by the author (2025) using Canva, synthesizing key concepts discussed in this essay. No copyrighted material was used.

II. Borders of the body – Autonomy, control, and biopolitics

The body represents a contested domain of power, identity, and control. Healthcare limitations determine who is permitted to consent, who is obligated to comply, and whose suffering is overlooked. Bioethics interrogates the authority over the body concerning health and autonomy. Authoritarian medicine marginalizes several individuals, with decisions dictated by the state, medical professionals, or family members. Feminist and disability campaigners emphasize that marginalized groups – women, individuals with disabilities, and those with mental illness – experience significant control and coercion.

Medical violence, like forced sterilizations and ignoring pain based on race or gender (Metzl, 2010), blurs care and control. Medical child abuse shows how safeguarding can mask coercion (Lawrence, 2000). These reflect biopolitical systems where healthcare enforces norms, assigns value, and sustains inequality (Beeckmans, 2014). Foucault’s concept of biopower explains how medicine regulates life beyond laws (Foucault, 1976), monitoring some while marginalizing others (Spade, 2011). As Franck Billé (2025) argues in Somatic States, the body itself often becomes a contested site where political, cultural, and spatial borders intersect, reinforcing how healthcare is rarely detached from broader power structures.

The body can be perceived as a geopolitical map segmented into regulated areas – uterus, brain, skin, genitals – where gender, racism, disability, and class converge (Petchesky, 2024). Healthcare serves not only as a means of healing but also as an instrument of power. In the absence of valuing autonomy, fairness, and empathy, particularly for marginalized populations, these obstacles will persist in determining who receives care and whose bodies merit dignity.

III. Virtual borders – Telemedicine and the digital divide

If the body represents the most intimate border, whereas the digital domain establishes concealed obstacles. Telemedicine has the potential to enhance healthcare accessibility; nonetheless, it remains inaccessible to many, exacerbating inequality. In isolated regions, inadequate internet connectivity, infrastructure, and devices render technology a hindrance. An Indonesian rural patient may be eligible for teleconsultation; but the absence of electricity, signal, or requisite skills renders access unattainable.

———————————————————————————–

A vignette – Mourning of a walk that has no trace

In a remote community health center in rural Papua, a midwife stares helplessly at a blinking laptop screen. The midwife’s frustration is palpable as she watches the blinking cursor, knowing every failed upload could mean a life lost miles away. Before her lies a pregnant woman suffering from severe bleeding, but unstable internet makes it impossible to send the ultrasound images to the referral hospital in the city. “We tried sixteen times,” the midwife sighs, “but only three attempts succeeded.” Without the ultrasound reaching the specialist, there would be no way to confirm life-threatening complications such as placental rupture or previa, both of which require urgent intervention and distinct management strategies to prevent maternal death.

In another village miles away, a young doctor resorted to sending a heart attack patient’s ECG through WhatsApp after the official telemedicine platform was too complicated and had failed him again — a desperate attempt to obtain rapid consultation before the patient deteriorated further. Without timely ECG interpretation, a potentially fatal cardiac arrest could occur before any referral or treatment plan is in place. “It’s like running a marathon with your legs tied,” he says.

———————————————————————————–

These cases illustrate how telemedicine, while promising connectivity, remains trapped in a digital labyrinth characterized by inadequate connectivity, unfamiliar interfaces, and functionalities that fail to meet local health requirements. Biopolitics 4.0: the state manifests through digital platforms yet fails to engage the populace due to inadequate infrastructure (Nugraheni et al., 2019). The gaps between data transmission and actionable care widen the very inequalities such technology aims to bridge.

As explored by Ahlin (2023) in Calling Family, digital technologies in healthcare, while promising connection, often reinforce existing social hierarchies, exposing the limits of telemedicine in contexts marked by infrastructural gaps and unequal digital literacy. Virtual healthcare presents ethical dilemmas with data ownership, privacy, and permission. Patient data frequently traverses corporate networks, posing risks of exploitation and reducing individuals to just data points, illustrating Agamben’s concept of the “state of exception,” when protections are lacking (Agamben, 2005). Telemedicine identifies symptoms but does not ensure recovery. Just as biopower regulates bodies, Amoore’s concept of the Deep Border (2024) further underscores how data infrastructures, often perceived as neutral, function as invisible yet powerful border regimes that govern access, identity, and risk in the digital health landscape. technopower dictates access. Virtual borders possess political authority comparable to physical ones, determining access to care and reducing lives to mere data. Despite assertions of neutrality, technology perpetuates disparities in race, class, geography, and citizenship. Telemedicine delineates access, benefiting certain individuals while marginalizing others (Kaufmann et al., 2009). In the absence of meticulous supervision, digital health exacerbates inequalities.

IV. Borders of care – Mobility, migration, and access in crisis

The boundaries of virtual healthcare have historically been disputed and influenced by external factors. Access is inconsistent, particularly during crises when borders restrict armies, ideologies, patients, and medical professionals. Access to care is contingent upon passports, regulations, and political factors. In regions such as Gaza, Rohingya camps, and Kalimantan/Malaysia, cross-border healthcare can be a matter of life or death. Some obtain emergency entry, while others encounter bureaucratic and political obstacles. The affluent get advantages from medical tourism, whilst millions of displaced or undocumented individuals encounter exorbitant expenses and restricted access.

The COVID-19 epidemic exposed disparities: affluent countries amassed vaccinations while impoverished nations faced difficulties. Lockdowns benefitted the affluent, who circumvented restrictions (Malachinska, 2024), whilst frontline workers in the Global South encountered prohibitions. The care provided exhibited bias (Reeve, 2016). Mobility justice (Sheller, 2018) illustrates how healthcare apartheid determines access to care and perpetuates suffering. In emergencies, borders prioritize and decide who receives medical care and who is abandoned. These territorial, digital, and biological boundaries overlap, creating complex exclusions. Denied care stems from interconnected barriers limiting autonomy, access, and recognition.

V. Intersecting borders – When digital, physical, and biopolitical borders collide

Envision a refugee at a national boundary, deprived of telemedicine and health information due to insufficient internet access. Physical boundaries impede mobility, whereas digital obstacles necessitate identification and consent, thereby eliminating undocumented individuals and those under duress. Access is contingent upon visibility and adherence to control systems.

When biopolitical authority exerts control over the body by coercion or the withdrawal of permission, virtual connectedness cannot reinstate agency. Patients devoid of autonomy are unable to completely utilize digital tools. Telemedicine exhibits bias, exacerbating existing physical and political disparities (Mol, 2009). These limitations mutually reinforce one another: a woman deprived of reproductive rights may encounter digital obstacles or legal repercussions (Rowland, 2019), whereas a disabled individual in a rural locale experiences geographic isolation and unavailable digital services, exacerbated by ableism.

Comprehending healthcare justice necessitates viewing boundaries not as discrete obstacles but as interrelated systems that generate cumulative exclusion. Oversight entities, movement restrictions, and digital space regulations result in systemic invisibility. Justice necessitates the removal of these borders and the redefinition of healthcare as a right upheld by solidarity rather than a commodity dispensed by permission.

VI. Conclusion – A world of layered borders

In the 21st century, healthcare transcends basic diagnosis and treatment; it is ultimately a problem of boundaries. The allocation of care, the individuals who experience delays, and those who vanish entirely are influenced by a complex network of biological, digital, and geopolitical obstacles. These borders do not function independently; they overlap, interact, and strengthen one another, establishing a reality in which exclusion is not incidental, but systemic. The border transcends a mere physical barrier between nations; it is embedded in data servers, marked on the body through biometric surveillance, and articulated in legal structures that delineate whose suffering is acknowledged and whose existence is mourned. A woman pursuing reproductive healthcare, a refugee lacking internet access, a disabled individual deprived of autonomy – each confronts a distinct barrier, yet all are intertwined inside the same framework of division.

Genuine healthcare justice necessitates more than enhanced access or improved funding. It necessitates the deconstruction of the structures that divide care based on power and privilege. We must not only eliminate national borders but also confront the divisions between body and data, presence and recognition, patient and individual. Reconceiving equitable care involves acknowledging that a body transcends mere flesh; it serves as a passport, a password, and a battleground. Until we address these complex barriers, the prospect of global health will remain unattainable for those still waiting at its entrance. Dismantling these volumetric boundaries requires cross-national solidarity, respect for bodily autonomy, and inclusive digital infrastructure. Only with that can health truly be a right, not a privilege.

———————————————————————————–

Coda – A poetic reflection, “Not a password, nor a gate”

They say I must be seen to heal

but the cameras never turn my way.

A signal blinks where no hands reach,

yet still, they call this care.

…

My name is missing from the dropdown menu,

my wound too blurred for the algorithm.

They ask for proof of body,

but I am already a border.

…

No code unlocks the clinic’s door

when silence is labeled illegal.

No app hears a scream

in a language not recognized.

…

But still, I wait

not as data,

not as burden,

but as proof:

that care begins

when no life is left behind.

References

Ahlin, T. (2023). Calling family: Digital Technologies and the Making of Transnational Care Collectives. Rutgers University Press.

Amoore, L. (2024). Deep Border: AI, Data, and the Global Security State. University of Minnesota Press.

Beeckmans, R. (2014). Alison Kafer, Feminist Queer Crip (Indiana: Indiana University Press, 2013), pp. 258, ISBN: 9780253009340, £16.99, paperback. Studies in the Maternal, 6(1). https://doi.org/10.16995/sim.11

Billé, F. (2025). Somatic States: Nations, Bodies, and the Politics of Borders. Duke University Press.

Kaufmann, D., Kraay, A., & Mastruzzi, M. (2009). Governance Matters VIII: Aggregate and Individual Governance Indicators 1996-2008. In World Bank policy research working paper. https://doi.org/10.1596/1813-9450-4978

Lawrence, J. (2000). The Indian Health Service and the sterilization of Native American women. The American Indian Quarterly, 24(3), 400–419. https://doi.org/10.1353/aiq.2000.0008

Malachinska, M. (2024). Problems of access to healthcare services in the armed conflict zones. Reproductive Endocrinology, 73, 8–13.

https://doi.org/10.18370/2309-4117.2024.73.8-13

Mol, A. (2009). The logic of care: health and the problem of patient choice. Choice Reviews Online, 46(08), 46–4482. https://doi.org/10.5860/choice.46-4482

Nugraheni, R., Sanjaya, G. Y., Putri, S. S. M., Fuad, A., Lazuardi, L., Pertiwi, A. a. P., Sumarsono, S., & Sitaresmi, M. N. (2020). Low utilization of telemedicine in the

First-Year trial: a case in the province of West Papua, Indonesia. Proceedings of the 4th International Symposium on Health Research (ISHR 2019). https://doi.org/10.2991/ahsr.k.200215.110

Petchesky, R. P. (2024). Abortion and Woman’s choice: The State, Sexuality and Reproductive Freedom. Verso Books.

Reeve, J. (2016). Borderlands: Towards an anthropology of the Cosmopolitan Condition.

Environment Space Place, 8(2), 144–147. https://doi.org/10.5840/esplace20168215 Rowland, A. L. (2019). The Right to Maim: Debility, Capacity, Disability by Jasbir K. Puar,

Duke University Press, 2017. Journal of Medical Humanities, 40(3), 455–458. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10912-019-09557-x

Spade, D. (2011). Normal life: administrative violence, critical trans politics, and the limits of law.

https://www.amazon.com/Normal-Life-Administrative-Violence-Critical/dp/0822360 403

The History of Sexuality. Volume 1: An Introduction: Michel Foucault : Free download, borrow, and streaming : Internet Archive. (2024, March 7). Internet Archive. https://archive.org/details/foucault-the-history-of-sexuality-volume-1

The protest psychosis: how schizophrenia became a black disease. (2010). Choice Reviews Online, 47(11), 47–6562. https://doi.org/10.5860/choice.47-6562