This work by Mia Tran is the second runner-up essay of the Eur-Asian Border Lab’s 2025 volumetric borders essay contest.

Mia Tran is a Vietnamese writer, activist, and student at New York University studying International Relations and Economics. As an SRH researcher for PAHO and youth advocate at the United Nations, she focuses on SDG 3 (Health and Well-being) and SDG 5 (Gender Equality), emphasizing community-rooted mental health and feminist policy. Through writing, she explores emotional landscapes and redefines vulnerability as a form of resistance and care. Through speaking, she amplifies overlooked truths and creates space for collective healing.

“Resilienza, generosità e gentilezza per coloro a cui è stata data l’opportunità di crearle per gli altri.” — Padre Don Mario Bellaveglia

JUNE 1979: My father, then only eighteen, drifted across the South China Sea, crammed among one hundred others in a creaking boat. Twenty days. No food. No compass. Just salt-burned skin and the memory of his sisters crying as he fled. They prayed not for land, but for mercy. For survival. For something beyond the horizon that didn’t smell like death.

He washed ashore in Deruta, Italy, where Father Bellaveglia gave him not only shelter, but a future. A second life. And, by extension, mine. His escape became my inheritance: not just a story of survival, but a lifelong question. What does it mean to belong when the ground beneath you has always been borrowed? His refugee status never left him. Not in how he saved broken things with glue and string. Not in how he never used the word “forever.”

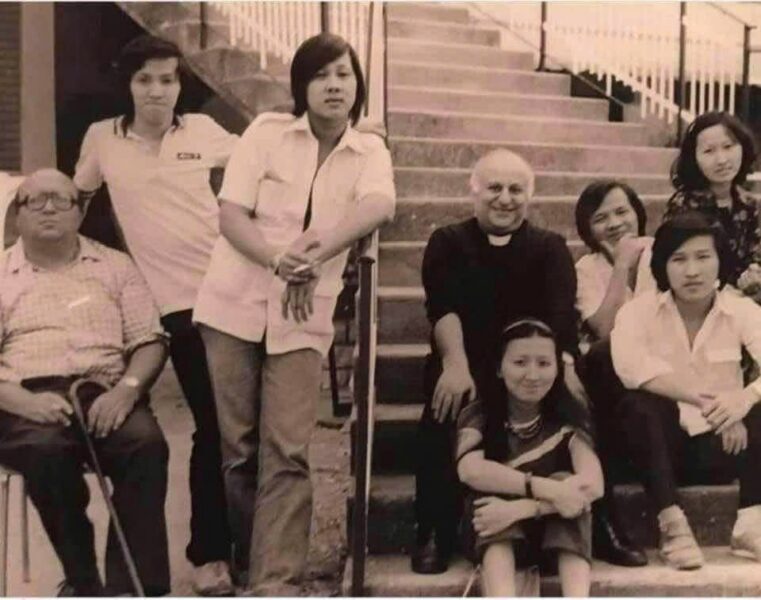

Captured a cherished moment in Deruta with my dad and his siblings alongside Father Bellaveglia. (Deruta, 1986)

MARCH 2005: My mother, then only thirty-five, pounded through the dusty streets of Saigon in four-inch heels. Each step was a sharp, deliberate, unapologetic cut through the morning haze. Her shoes clapped like thunder against the pavement, warning the world not to underestimate her. She didn’t have maps or mentors, only a chipped phone and the will to negotiate business deals no one believed she could close. While my father stayed home, hands covered in dish soap and oil paint, my mother became our shield, our storm. They told her to shrink. She chose stilettos.

My mother takes the time to care for me after her long 10-hour shift as a construction contractor (Saigon, 2009)

Raised by a refugee father and a mother who shattered gender roles, I was a borderland child before I knew what borders were. My mother’s heels click-clacked ambition; my father’s silence hummed with exile. They never asked me to choose between them, but the world did.

I internalized my father’s quiet resilience and my mother’s fire, caught between their contradictions. In place of bedtime stories, I prayed to Buddha, absorbing the principle of nondualism: that the self and the world are not separate. Yet school, society, and even the language around success drew sharp boundaries I couldn’t ignore. What I felt and what I was expected to be often collided. I didn’t yet have the words for it, but I was living within a bordered identity.

That identity took shape not just between cultures, but between tongues. Some parts of me existed only in Vietnamese: a language of nuance and softness. Other parts, learned in English, were urgent and assertive. In Italian, I shrink into silence. Between these languages, I often felt like a ghost walking between rooms, fluent in all but at home in none. Language, like identity, is never fixed. Each tongue opens a different doorway into myself: each a border, both confining and expansive.

As I moved between these worlds, I began to notice that it wasn’t just language or culture that drew boundaries. It was stigma. I once believed stigma was simple. Vietnam’s silence around mental health? Culture. America’s openness? Progress. That belief shattered when I heard an American doctor confess he avoided therapy, afraid of losing his medical license. Later, I found out some U.S. states still allow employers to ask about mental health history. So much for progress.

Suddenly, stigma wasn’t cultural. It was systemic. Embedded not only in social shame, but in policies pretending to protect while quietly excluding. And what unnerved me most wasn’t just the rules; it was how easily the systems I trusted, like social work and shelters, mimicked the same power dynamics they claimed to resist. I’ve seen “help” offered like judgment. I’ve seen safety feel like surveillance.

In Vietnam, my cousin’s depression was treated as spiritual punishment. She was made to kneel, pray, fast as if her sadness were a curse to be exorcised. In America, I saw the same erasure dressed in clinical terms. What changed was the costume, not the consequence.

That realization didn’t make me bitter. It made me hungry to understand. I began to ask: who are these systems really for? What stories have we normalized? What possibilities have we never dared imagine?

The Altar of Contradiction/ Place: Saigon, Vietnam Year: 2023

|

This is where my family once gathered. Over fifty monks from across Vietnam to chant for hours, offering prayers and incense to restore my grandmother’s health. For her, the rituals were love. But when my cousin showed signs of depression, she was told to kneel and pray one thousand times, not as care, but as correction. This temple held both healing and harm. The boundary between spiritual devotion and systemic superstition blurred, revealing how stigma can hide beneath even the most sacred intentions. |

Those questions led me to create my own space.

Lặng (Solitude) began with a single letter I pinned to a white wall: a question to my mother about all we never said. Within days, thousands of strangers responded, filling the gallery with Post-it notes. But they didn’t name cities or borders. They wrote of longings, grief, and memories they had hidden even from themselves. Families came together and wept. Children pointed out their parents’ secrets with wide, wondering eyes. What began as art became a sanctuary.

Lặng (Solitude) began with a single letter I pinned to a white wall: a question to my mother about all we never said. Within days, thousands of strangers responded, filling the gallery with Post-it notes. But they didn’t name cities or borders. They wrote of longings, grief, and memories they had hidden even from themselves. Families came together and wept. Children pointed out their parents’ secrets with wide, wondering eyes. What began as art became a sanctuary.

Lặng wasn’t a place. It was a volume: a space suspended between people, held together by silence unraveling into speech, into presence, into truth. There, healing happened not through advice, but through being seen.

That moment redefined my understanding of borders. Emotional well-being is not a solo journey. It is relational, shaped in spaces where vulnerability is honored, not punished.

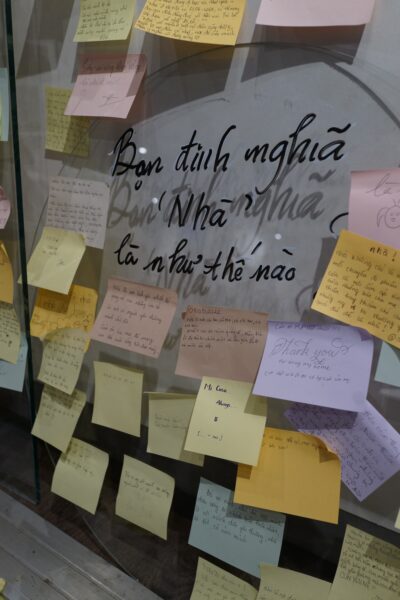

(Saigon, 2022) Letters to Home: A wall installation from my exhibition Lặng (Solitude) features anonymous handwritten responses to the question “What does ‘home’ mean to you?” The exhibition invited public reflection in the form of Post-it notes, which were added over time by visitors of all ages. The responses, ranging from single words to deeply personal stories, create a layered and communal archive of lived emotional experience.

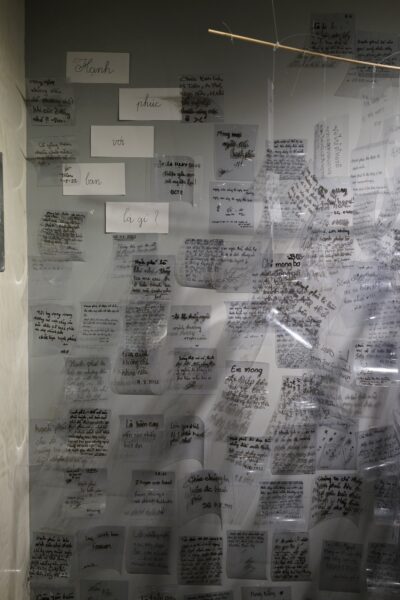

I saw this in action through my work in my organization “Tôi, Chúng Ta,” (I, We) where I translated Western psychology texts and saw their failures. How could we talk about “happiness” when our language lacked the words to describe communal peace or ancestral grief? Inspired by Dr. Tim Lomas, I helped participants in Lặng invent new words: neologisms for mixed emotions, for joy intertwined with sorrow, for the peculiar relief of being understood at last.

In those moments, I was no longer a translator. I was a cartographer of emotional geographies. Each word we created was a border crossed, a silence broken, a new way to be together.

And still, a question lingered: What if identity isn’t linear? What if it’s volumetric? A layered, porous space rather than a bounded state?

To be the daughter of a boat refugee and a breadwinning woman, to have translated psychological terms into languages that didn’t have them, to have curated pain into poetry; this is not a single story. It’s an ecosystem. A borderless atlas of self.

(Saigon, 2022) Defining Happiness: Another wall from my exhibition Lặng (Solitude), where visitors responded to the prompt “Hạnh phúc với bạn là gì?” (“What does happiness mean to you?”). The responses, written in Vietnamese, English, or hybrids of both, revealed how language shapes, limits, and sometimes liberates the way we understand well-being. Many participants used metaphors, invented new words, or described emotions that didn’t have a direct translation. This became a living archive of culturally specific definitions of happiness, beyond textbook psychology or Western frameworks.

My family and I celebrate the Lunar New Year in Vietnam after my dad’s migration (Saigon, 2024)

I am Vietnamese and Italian, but also something unnamable that stretches between them. I am shaped by the rhythms of Saigon, the quiet of Deruta, the electric pulse of New York. My accent changes depending on who I’m with. My values shift like riverbanks, but my anchor is always compassion.

Just as nondualism rejects separation, I believe policies, systems, and social frameworks must do the same. We cannot build effective mental health programs or refugee services without recognizing the interplay between economics, language, and spirit. Healing isn’t about isolation; it’s about interdependence.

The sound of my mother’s heels no longer echoes as pressure. They echo as rhythm, a legacy I honor in my own steps.

The borders I inherited, across seas, systems, and silences, aren’t fixed. I am learning to rewrite them. To soften them into stories, into shared sanctuaries like Lặng, into questions that don’t demand answers but invite us to listen.

This essay is not a conclusion. It is a portal. A prayer.

And maybe, just maybe, the borders we challenge today won’t have to be inherited tomorrow.

Photo credits: The first image (Deruta, 1986) is courtesy of my uncle, Anh Tuan Tran. All remaining photographs are from the personal archives of myself and my father, Anh Dung Tran.