As a part of the symposium ‘Bridging the Regions and Disciplines in Border Studies’, this exhibition presents photos taken by scholars in territorial borderlands of Europe and Asia. Conceived by humans, political borders are rigid, fixed lines on maps, reinforced by fences, gates and guards and strengthened through discourses on statehood and sovereignty. In lived borderlands, we can see interconnected voluminous spaces linked by human activity, wandering animals, the circulation of water and air. Contemporary borderlands are produced through multiple narratives, performances, and practices, which come in myriad orders and colors. Borders are lines that live.

|

|

| Mélanie Sadozaï. River as a border between Tajikistan and Afghanistan, 2014 |

Mélanie Sadozaï. Bridge connecting Tajikistan and Afghanistan, 2021 |

Often, natural bodies such as mountains and rivers provide a convenient landmark for designating political borders. For instance, the Pyanj River marks the border between Tajikistan (on the left bank) and Afghanistan (on the right bank). The photos, which Mélanie Sadozaï took in the district of Ishkashim and the village of Ruzvai (both from the Tajikistan side), show the river and bridge both connecting and separating the two contemporary states.

|

|

| Uttam Lal. Thin air of the India-China borderscape in north Sikkim, India, 2017 |

Olga Cielemecka. Białowieża Forest in the Poland-Belarus borderlands, Hajnówka county, Poland, 2022 |

Conceptual borders cut through connected spaces. For instance, Olga Cielemecka explores the Białowieża Forest, a transboundary heritage forest in Poland and Belarus. During the winter and spring of 2022 when she took the photo, the area of this relic forest was waterlogged after the winter thaws. Mossy branches and rotting logs, massive puddles and the submerged roots of oaks, hornbeams and pines formed a vibrant, tangled web in this border area. Uttam Lal captured the landscape of the India-China borderlands in north Sikkim noting that the border needs to be experienced though its thin air. These photos demonstrate that what we may perceive as a pristine natural view, in reality, is imbued with political meanings, state power, and geopolitics.

|

|

| Jussi Laine. The walking path from Séez at the France-Italy border, 2022 | Jussi Laine. Bicycle parked at Tarvisio/Trbiz in the Italy-Slovenia borderlands, 2023 |

Territorial borderlands are diverse. Some feature manifestations and practices of state territoriality, such as the small concrete marker with ‘F’ for France found on a hiking trail crossing into Italy, or the border marker serving to prop up a bicycle in Jussi Laine’s photos. On the other hand, crossing some borders can be deadly, as the sign in one of the photos by Willem van Schendel alerts passersby of a minefield across China’s border with Myanmar. Attesting to the complexity of space-making at international borders and the hollowness of many state claims to territorial control, the ‘other side’ is controlled by Myanmar’s military regime (on the left) and a powerful armed resistance group (on the right).

|

|

| Willem van Schendel. Minefield on the China-Myanmar border, China, 2023 | Willem van Schendel. Theme park on the China-Myanmar border, China, 2023 |

These spaces contrast with the theme on Willem van Schendel’s other photo. It shows a theme park, known as “One Village Two Countries,” located along a different section of the same border. It caters to Chinese tourists who can see miniature pagodas and sculptures of elephants as well as observe everyday life in Myanmar through a wire fence. The image of cross-border harmony and amity radiating from the park contrasts with the fierce fighting between the Myanmar army and resistance forces, thereby highlighting the intensity and unevenness of life along the border.

|

|

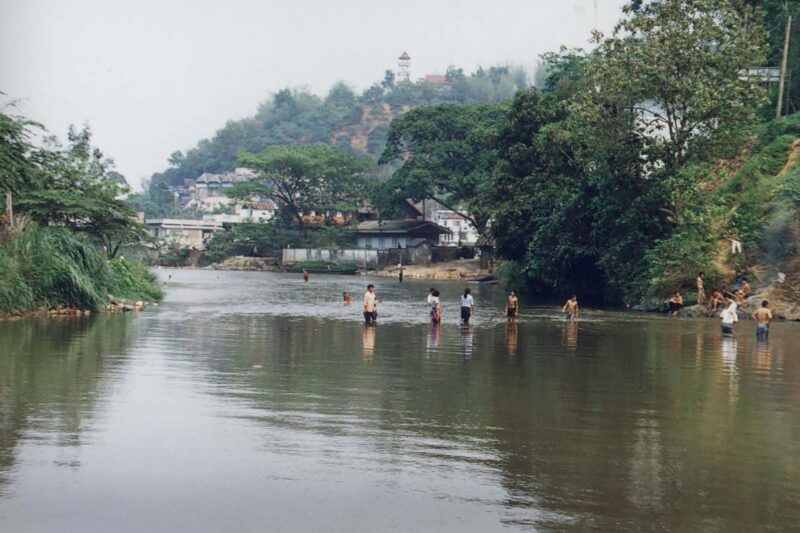

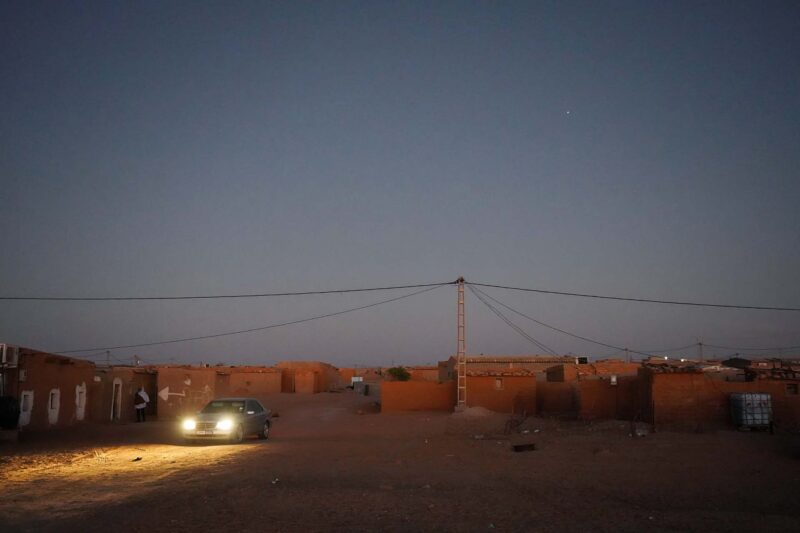

| Ariel Sophia Bardi. Ausserd refugee camp in Algeria near the Morocco-Western Sahara-Mauritania border, 2022 | Saara Mildeberg. Omalo, a Tush village near the Georgia-Russia border, 2023 |

Political borders can be mundane spaces where people live. Ariel Sophia Bardi and Saara Mildeberg explore quite different settlements – the Ausserd refugee camp in Algeria at the edge of the Moroccan and Mauritanian borders and the Omalo village on the Georgia-Russia border – which both share similar struggles with extreme isolation and a state of being bordered-in.

The everyday life of the Saharawi refugees from Morocco-controlled Western Sahara is vulnerable to the desert’s harsh climate. Frequent sandstorms and floods strain local infrastructure. Although the camp is connected to the electricity grid, car headlights are sometimes the only source of light at night. The Omalo village in Georgia was cut off from the electricity grid after the Soviet Union’s collapse which left it on the border between the two now-independent states. Today, the villagers power their houses with solar panels and diesel generators, whereas in the winter, most relocate to the lowlands due to road conditions – from late October to early June, Tusheti is only accessible by helicopter.

|

|

| Karin Dean. Trespassing the China-Myanmar border, Ruili city, China, 2000. | Alessandro Rippa. Trading cigarettes across the China-Myanmar border, Ruili city, China 2015. |

People often find creative and resourceful ways to navigate or exploit border infrastructure. In 2000, Karin Dean photographed a young woman crossing from China to Myanmar through a hole in a fence, showing that this is an everyday practice for locals. In 2015, Alessandra Rippa observed how the same fence was effectively used to trade cigarettes, exploiting the price difference between the two countries.

|

| Asel Murzakulova. Dust on the road used to bypass state borders in the Ferghana Valley, Kyrgyzstan-Uzbekistan borderlands, 2019 |

Local borderlanders often know how to bypass border policies and infrastructure. Exploring the Kyrgyzstan-Uzbekistan borderlands in the Fergana Valley, Asel Murzakulova photographed the dust on a road used for illegal trade. During the era of closed borders, tall trees thrived along this route, concealing both dust clouds and the existence of roads that can facilitate border bypasses.

Despite infrastructural and political boundaries, everyday life on the border has its small joys. For instance, Karin Dean observed how locals beat the heat of the tropical climate in the shallow border river between Mae Sai, Thailand and Tachilek, Myanmar. Similarly, Asel Murzakulova photographed children in a village along the Kara-Darya River. For them, the transboundary canal does not embody the high politics of water management between states but is a source of delight and entertainment.

This exhibition features works by border scholars who use photography in their fieldwork. Some of them have a dual identity as both academics and photographers, while others have discovered the benefits of this tool through extensive practice. Photography as a visual ethnographic tool allows for the capture of nuanced details, expressions, and spatial relationships, which are often difficult to pin down in words. Photographic images can capture and express the intangible and convey moods, feelings, emotions, and atmosphere. Photography also reflects both the scene and the person who is taking the picture, as it shows the photographer’s interests and perspective. The visual dimension can enrich the understanding of the subject matter and aids in a more comprehensive interpretation of field material. Often, photos act as a visual diary or memory capsule later providing details that might have been overlooked during the fieldwork.

Photographs can be used to communicate with those portrayed in the photo, given as a gift, and presented in the academic domain for both publications and presentations. Thanks to contemporary digital formats, photos are easy to share, edit, and discuss with people all over the world. Yet, sometimes, analogue printed photos can be wonderful artifacts, which serve as an ice-breaker between researchers and their counterparts during the fieldwork. Furthermore, photographs along with text create narratives which can effectively convey complex and diverse stories, such as those from border regions. In this way, photography is a powerful tool to disseminate academic knowledge and scholarly observations in a visually expressive format accessible to broader audiences.

Participants:

Asel Murzakulova is a Senior Research Fellow with the University of Central Asia’s Mountain Societies Research Institute and Co-Founder of the analytical club “Mongu”.

Ariel Sophia Bardi is a writer, photographer, and researcher focused on culture and human rights with an emphasis on visual and spatial cultures. She is adjunct faculty at Temple University Rome and has led documentation missions for the United Nations.

“Photographs are more than illustration; they are visual ethnographies and image-narratives.”

Mélanie Sadozaï is a post-doctoral fellow at the Institute for European, Russian, and Eurasian Studies (IERES) of the George Washington University.

“Photography is a means to redirect attention to everyday life at the border. By taking pictures, I seek to show that the border between Tajikistan and Afghanistan is far from being a zone of chaos and disorder.”

Willem van Schendel is a professor at the International Institute of Social History of the University of Amsterdam who works in the fields of history, anthropology, and sociology of Asia.

“I have always used photography extensively during my research, from village fieldwork when I was a master’s student to an island-hopping tour last month”

Uttam Lal is an Assistant Professor of Geography at Sikkim University who works in the Himalayan ecology and borders.

Karin Dean is a senior researcher at Tallinn University’s School of Humanities who focuses on the political geographies of Myanmar’s borderlands and Kachin spatialities across China, Myanmar and India.

“I feel privileged that I have the opportunity to see the places and take part in people’s lives, during fieldwork, and feel that photos are a way of capturing these precious experiences.”

Saara Mildeberg is a documentary photographer and a junior researcher at the Centre for Landscape and Culture at Tallinn University.

“Similarly to words, photography reflects both the picture-taker and their subject, by revealing what is paid attention to, how is it framed, and by whom.”

Alessandro Rippa is a social anthropologist at the University of Oslo, interested in issues surrounding infrastructure, borders, globalisation, conservation and the environment, particularly in the contexts of the China-Myanmar borderlands and the Italian Alps.

“I noticed that the very act of taking pictures showed me a different side of what I was seeing”

Olga Cielemecka is a postdoctoral researcher at the Department of Social Sciences, at the University of Eastern Finland. Her research brings together contemporary philosophy, feminist and queer theory, environmental humanities, and critical border studies.

Jussi Laine is a professor of multidisciplinary border studies at the Karelian Institute of the University of Eastern Finland, holding the title of Docent of Human Geography at the University of Oulu, Finland.

The exhibition LINES THAT LIVE is organized by Eur-Asian Border Lab.

Curatorial team: Karin Dean, Aleksandra Ianchenko, Krista Mölder,

Exposition design: Aleksandra Ianchenko, Krista Mölder

Web version: Djahane Ambrine Zaïr

Coordination: Sevda Özden