By Tümüzo Katiry, Kevide Lcho, and Saktum Wonti

Canada-IDRC Myanmar Research Fellows, The Highland Institute, Kohima, Nagaland

Introduction

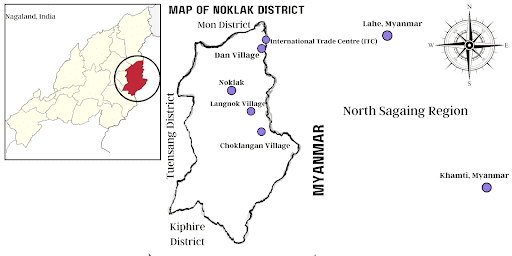

Map of Noklak District, Nagaland

Standing at the Indo-Myanmar border, in the formidable hill country of the Khiamniungan Naga tribe, you will be captivated by the beautiful landscape and the lush fields. But before long, you find out that the fields are in Myanmar and the farmers are in India. The borderline bisects their ancestral land, splitting it between two states.

Four northeastern states in India—Arunachal Pradesh, Nagaland, Manipur, and Mizoram—share a 1643-km-long border with Myanmar’s Kachin State, Sagaing Region, and Chin State. In Nagaland, four districts—Mon, Phek, Kiphire, and Noklak—hug the international border. In all these districts, the boundary divides the indigenous people. Noklak District is inhabited mainly by the Khiamniungan tribe. However, Noklak represents just a small portion of Khiamniungan territory. There are around 200 Khiamniungan villages in total; approximately 50 lie within Noklak District, India, while 150 are located within the Sagaing Region of Myanmar.

To understand the lived reality at the borderlands, it is vital to realise that the international boundary was arbitrarily imposed. No tribal leaders were consulted during the demarcation or informed of it. As it remained a porous border with no fencing, the villagers were oblivious to its existence until border pillars appeared on their land (Ketoukhrie-ü, 2023). ‘We were not aware of the boundary demarcation. It was only when the missionaries from India came to our village [that] we learned about the grim reality’, said Mr. Lam, who hails from a village in the Sagaing Region.

The abandoned border construction at Dan Village

We visited Noklak during the Earthkeepers project, based at The Highland Institute, Kohima, and funded by the International Development Research Centre (IDRC) of Canada. Our task was to document traditional ecological knowledge and perceptions of climate change along the Myanmar-Nagaland border. During fieldwork, the villagers told us about frequent conflicts with the Assam Rifles personnel patrolling the border. This should not be surprising. For the Khiamniungans, the border obviates their preexisting social reality. Hence, the villagers strongly resisted the demarcation, dismantling the border pillars and even destroying barricades made by the military.

An imaginary line from border pillars 139 to 146 separates the Khiamniungan in India from their relatives in Myanmar. In 2017, an attempt by the Indian and Myanmar governments to fence the border met with vehement local opposition (Morung Express, 2017). The proposed fence would have sealed off access to 3,500 acres of agricultural land, and the village councils argued that 10,000 villagers (the total includes people on both sides of the border) would be left without a livelihood (Business Standard, 2017). Following the protest, the Indian Central Government stopped the fencing (The Indian Express, 2017). Today, near Dan Village (see map), the abandoned concrete structure stands like an ugly row of jagged teeth, scarring the golden hillside.

Understanding the Naga-Myanmar Borderland

Dan villagers’ jhum fields in Myanmar

The Indo-Myanmar boundary along the magnificent Patkai range is an arbitrarily imposed borderline planned and manoeuvred by British colonial administrators and accepted by the post-colonial states of India and Myanmar (Burma at the time). (Ketoukhrie-ü, 2023). Historically, the Patkai was a contested area with many indigenous communities, including the Nagas, who fought regularly among themselves.

The daily struggles of communities in these borderlands can be usefully viewed through the lens of border politics. The region is a locus of contestation where India, as a sovereign state, attempts to consolidate territory through symbolism while the indigenous community resists by establishing bilateral relationships and undermining state policies. For instance, the Khiamniungan Tribal Council (KTC) opposed the construction of the physical border demarcation with the support of other Naga tribal bodies (Nagaland Post, 2017).

Local opposition arises mainly because the border is separating the community from the land for jhum1 cultivation. In addition, because most of the Khiamniungan villages fall under Myanmar, as explained above, the border disrupts the free movement of the people through their historical tribal territory. When we asked how the villagers felt about the soldiers patrolling their land, an informant said: ‘We protested against the tight security at the border; we told them that we would not allow them to stay in our land if they were constantly interrogating and checking the locals crossing the border. It is not very strict now’.

Life on a porous border

The Indian and Myanmar governments have established the Free Movement Regime (FMR) to enable interaction and economic exchange between borderland communities. The FMR permits tribes residing along the border to travel 16 kilometres across the boundary without visas. Usually, there are no restrictions on border movement either way, and people often cross without permission. This porous border also facilitates illegal trade and drug trafficking.

The movement of people across the Indo-Myanmar border is catalysed by Myanmar’s unstable governments and has left the country’s northwest region largely neglected. Indigenous communities, therefore, continue to establish close economic relations with their counterparts in India, who tend to be somewhat more secure.

State neglect on the Myanmar side has fostered another problem for the borderland communities. The mountains and forests of Sagaing provide havens for various militant groups, whose activities threaten the security and economy of the local people, as we will see below.

Borderland Economy

Villagers in Sagaing (see map) rely on Noklak town in India and Lahe and Hkamti in Myanmar for basic amenities. Some villages do not have shops, forcing people to commute for about three hours by motorcycle to the nearest town. However, due to high transportation costs, even by motorcycle, many opt to walk across the mountains, and it may take them a day or more to reach major towns. A young woman we interviewed said:

“We go to our village via Choklangan. There are bikes [motorcycles] reaching the village now, but we don’t really have money to hire one. We have to start at 2 or 3 a.m. to reach before midnight. The mountains get covered in snow in winter, and there are a lot of things to carry—from food to blankets. It is not very easy, but we have to keep walking to keep ourselves warm. I remember one year during the Christmas season, as I was returning from the village with my brother, the Assam Rifles were at the border. They asked us a few questions and checked our belongings. We were young back then, and it was really scary. You get used to it over the years.”

An International Trade Centre (ITC) on Dan Village land was inaugurated by the Government of Nagaland with support from local people with the aim of making it one of the border’s main trading hubs. However, the project failed due to local disputes and clashes between the Indian Army and various militant factions.

No metalled roads cross the border here, so goods and people move mainly by motorcycle. The two-wheelers, of a particular design, are made in Myanmar; they have no registration plate and cannot go further into India than Noklak District. Local entrepreneurs operate motorcycle taxi services between Noklak and the Myanmar Khiamniungan villages. Our guide, who runs such a service, told us that around 50–100 motorcycles cross the border from Noklak District daily, primarily from Dan, Langnok, and Choklangan Villages (see map).

LEFT: Motorcycle en route to Supao village (Myanmar), Indian section -Photo courtesy Mr Lam

RIGHT: Motorcycle en route to Supao village (Myanmar), Myanmar section -Photo courtesy Mr Lam

We tried to assess the volume of goods moved by bike across the border, but it proved too difficult. A bike can carry up to 100 kg of items in good weather. However, during monsoons, the mountainous terrain is too dangerous for two-wheelers, which greatly affects trade.

Larger-scale commercial export and import between Noklak District and Myanmar can take place only via Dan Village (see map) because Dan has the only cross-border road in Noklak where two-axle vehicles (mini-trucks) can travel. The exports from India are mainly food items, especially rice, oil, cereals, milk powder, and sugar. Construction materials for Myanmar are brought from the towns (Noklak, Lahe, and Hkamti), but transporting materials in quantity from Noklak becomes difficult due to the road conditions.

Petrol and diesel are in high demand in Myanmar. A litre of petrol can cost up to 7500 kyats (which is around 300 INR)—about three times the price in Nagaland state. Rice, the staple, can even cost up to 3000–5000 INR per rice bag (50 kg)—more than twice its value in Nagaland. Items travelling east to west depend primarily on what people in the Noklak region demand, with the most common items being hunting boots, daos (Naga machetes), spears, and agricultural equipment.

Any political and internal conflict within the Khiamniungan community, especially between those in India and Myanmar, can cause border closures at Dan Village. This poses a problem for villagers from Myanmar, who have become even more dependent on Indian goods since the 2021 military coup. A few months after our visit to Noklak, large-scale trade via Dan was stopped, but people still cross the border on motorcycles through Langnok and Choklangan to buy and sell. Resolving community conflicts is important because the inability to do business in Myanmar has forced Sagaing residents to trade in Noklak. In addition, as we saw during fieldwork, many young boys are compelled to go to Noklak to earn daily wages because their parents lost their income source in the post-coup economic crash. The boys are paid 200 INR per day, less than half the daily wage in Kohima.

Conclusion

The Noklak region, adjacent to the Myanmar border, presents an intriguing fusion of stunning natural landscapes, rich cultural heritage, and captivating off-the-beaten-path experiences. It is truly remarkable to witness the villagers crossing an international border as part of everyday life—visiting family, harvesting crops, and shopping in another country.

The imposed border has an immense impact on the borderland communities, as they experience in-betweenness in all its forms. They struggle to keep the community intact by protesting against state policies that attempt to divide them. It is not uncommon for Noklak people to help their Myanmar counterparts access Indian state facilities that are difficult to obtain in Myanmar. We found that local attention is focused on economic activities, favourable bilateral relations, education, health, and social development. Our informants expressed hopes for a better future, including eco-tourism development, to help them leave trauma behind and enjoy their magnificent mountains in peace.

Notes

- Jhum cultivation is a traditional farming practice involving clearing the land of trees and other vegetation, burning it, and then planting subsistence crops like rice, maize, millet, yams, and vegetables. The ashes from the burned vegetation provide essential nutrients for the soil. After a few years of cultivation on the same plot, the soil fertility decreases, and the farmers abandon the land and move to a new patch of forest to repeat the cycle.

REFERENCES

Business Standard (2017, January 1). Naga villagers protest loss of 3,500 acres of arable land to border fencing. Retrieved on July 8 https://www.business-standard.com/article/news-ians/naga-villagers-protest-loss-of-3-500-acres-of-arable-land-to-border-fencing-117010100245_1.html

India. (1943). Government of India Act, 1935. New Delhi.

Nagaland Post. (2017, February 16). KTC applauds solution to DAN ITC Pangsha. Nagaland Post. Retrieved July 7, 2023, from https://nagalandpost.com/index.php/ktc-applauds-solution-to-dan-itc-pangsha/

Nagaland Post. (2017, February 16). KTC applauds solution to DAN ITC Pangsha. Nagaland Post. Retrieved July 7, 2023, from https://nagalandpost.com/index.php/ktc-applauds-solution-to-dan-itc-pangsha/

The Geographer. (1968, May 15). International Boundary Study. No. 80, Burma–India Boundary (Country Codes-BM-IN). Offices of the Geographer, Bureau Intelligence and Research. http://www.lwa.fsu.edu-IBS

The Morung Express (2017, February 10) Myanmar border fencing stopped along Nagaland_ CM T R Zeliang _ India News, The Indian Express. (2017). The Indian Express. Retrieved on July 8 https://indianexpress.com/article/india/myanmar-border-fencing-stopped-along-nagaland-cm-t-r-zeliang-4512898/

The Morung Express. (2017, January 2). Policy to separate Naga lands questioned | MorungExpress | morungexpress.com. The Morung Express. https://morungexpress.com/policy-separate-naga-lands-questioned

Ukhrul Times. (2023, June 14). Nagas In Myanmar Condemns Factional War; Warns of Non-cooperation, Withdrawal of Support. Ukhrul Times. https://ukhrultimes.com/nagas-in-myanmar-condemns-factional-war-warns-of-non-cooperation-withdrawal-of-support/

Tümüzo Katiry, Kevide Lcho, and Saktum Wonti are Canada-IDRC Myanmar Research Fellows, based at The Highland Institute, Kohima, Nagaland. https://highlandinstitute.org/2023/03/10/earthkeepers/

Tümüzo Katiry has an M.Sc. in Anthropology from Kohima Science College; Kevide Lcho has an M.Sc. in Agriculture Extension Education and Communication from Sam Higginbottom University of Agriculture, Technology and Sciences: and Saktum Wonti has an M.Sc. in Anthropology from Sikkim University.